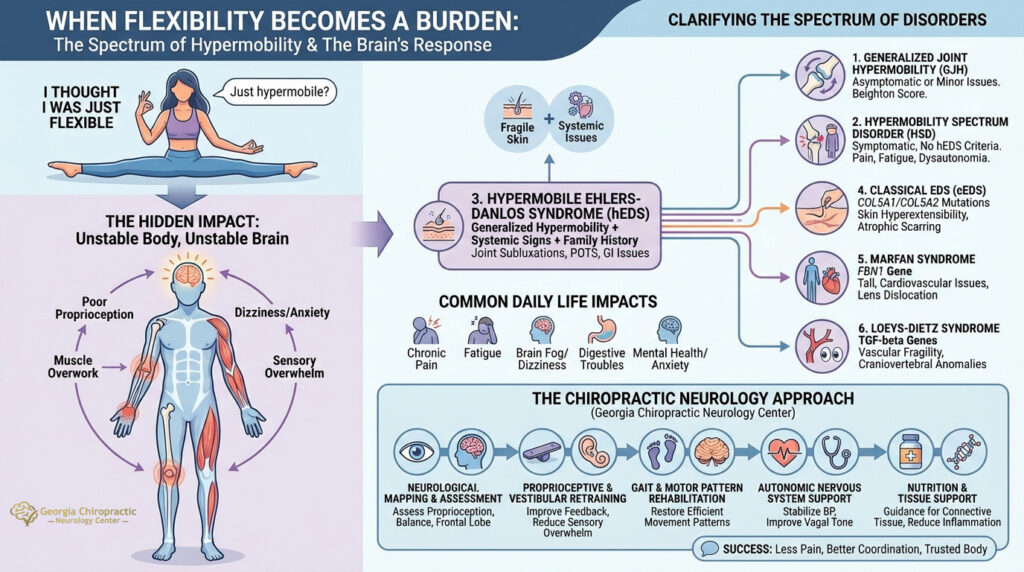

“I Thought I Was Just Flexible”

You have always been able to touch your toes, do the splits, or bend your fingers in unusual ways. Maybe people joked that you should have been a gymnast. But lately, you are not laughing—your joints ache, you tire easily, and your body does not seem to hold itself together. You have seen multiple doctors, had blood tests and MRIs, but no one has connected the dots.

If you have been told you’re “just hypermobile,” it is time to dig deeper.

At Georgia Chiropractic Neurology Center, we understand that hypermobility is not a one-size-fits-all condition. Behind flexible joints often lies a complex interplay of connective tissue dysfunction, neurological instability, and systemic symptoms that go far beyond bendy fingers. And the label “Ehlers-Danlos” is just one part of the story.

When the Body Feels Unstable, the Brain Follows

While the outward signs of hypermobility may seem harmless—or even enviable—what many people do not see is the internal sense of instability it creates. Joints that move too much can make muscles overwork to compensate. Ligaments may not provide the feedback the brain relies on for proprioception. This often leads to fatigue, poor coordination, frequent injuries, dizziness, and even anxiety or sensory overwhelm.

While the outward signs of hypermobility may seem harmless—or even enviable—what many people do not see is the internal sense of instability it creates. Joints that move too much can make muscles overwork to compensate. Ligaments may not provide the feedback the brain relies on for proprioception. This often leads to fatigue, poor coordination, frequent injuries, dizziness, and even anxiety or sensory overwhelm.

This is not just about collagen or loose joints—it is about how your brain processes movement, posture, and safety.

Clarifying the Confusion: There Is More Than Just Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

The most common condition associated with hypermobility is Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS)—particularly the hypermobile type (hEDS). But many people with hypermobility do not meet the diagnostic criteria for EDS. And others may be dealing with different, though overlapping, syndromes altogether.

Let’s look at the main hypermobility-related conditions and how they differ:

1. Generalized Joint Hypermobility (GJH)

- Definition: Increased mobility of multiple joints without systemic symptoms.

- Diagnosis: Based on the Beighton Score (a measure of joint mobility) and clinical history.

- Impact: Often asymptomatic or causes minor issues like sprains or fatigue after exercise.

- Neurological Consideration: May still cause altered proprioception and increased fall risk in certain individuals.

2. Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder (HSD)

- Definition: A group of diagnoses for people with symptomatic hypermobility who don’t meet criteria for hEDS.

- Subtypes: Includes generalized HSD, localized HSD, and historical HSD (when joint hypermobility was present in youth but has since lessened).

- Symptoms: Joint pain, instability, fatigue, dysautonomia symptoms, anxiety, and proprioceptive dysfunction.

- Diagnostic Criteria: Based on 2017 International Consortium guidelines—ruling out hEDS and other causes while confirming symptomatic hypermobility.

- Neurological Angle: Often shows midbrain upregulation, poor balance, and autonomic dysfunction.

3. Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS)

- Definition: A subtype of EDS with generalized hypermobility and systemic involvement.

- Diagnostic Criteria (2017): Requires all of the following:

-

- Generalized joint hypermobility

- Two or more of the following: systemic manifestations (skin involvement, hernias, prolapse), positive family history, musculoskeletal complications

- No exclusionary conditions

- Symptoms: Joint subluxations, skin fragility, gastrointestinal dysmotility, migraines, POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome), fatigue, anxiety.

- Neurological Viewpoint: Frontal lobe fatigue due to overcompensating for poor motor maps, chronic stress activation, and sensory hypersensitivity.

4. Classical EDS (cEDS)

- Definition: A genetically distinct form with confirmed COL5A1 or COL5A2 mutations.

- Key Features: Skin hyperextensibility, atrophic scarring, joint hypermobility.

- Less Common but More Severe: May involve tissue fragility, cardiac concerns.

- Neurology Consideration: Though not always symptomatic neurologically, instability may contribute to balance and coordination difficulties.

5. Marfan Syndrome

- Definition: A connective tissue disorder involving the FBN1 gene.

- Key Features: Tall stature, long limbs, cardiovascular abnormalities (e.g., aortic aneurysm), lens dislocation.

- Joint Hypermobility?: Present but usually less symptomatic than in hEDS or HSD.

- Neurology Connection: Risk of dural ectasia (spinal fluid sac enlargement), scoliosis, and coordination issues due to skeletal anomalies.

6. Loeys-Dietz Syndrome

- Definition: A rare, aggressive connective tissue disorder involving TGF-beta signaling genes.

- Symptoms: Vascular fragility, wide-set eyes, bifid uvula, skeletal hypermobility.

- Distinction: Higher risk of arterial rupture than Marfan or EDS.

- Neurological Risk: Spinal instability and headaches may occur from craniovertebral anomalies.

How These Conditions Affect Daily Life

Regardless of diagnosis, the lived experience of hypermobility syndromes often includes:

- Chronic Pain: From overuse, subluxations, or muscle guarding.

- Fatigue: Due to constant muscular compensation and dysautonomia.

- Dizziness & Brain Fog: Often tied to POTS or other forms of dysautonomia.

- Digestive Troubles: Due to connective tissue laxity in the GI tract.

- Mental Health Impact: Anxiety and sensory overload are common, partly due to midbrain and limbic overactivation from physical instability.

This is not just about collagen—it is about how your brain interprets a body that does not feel secure.

The Chiropractic Neurology Approach

At Georgia Chiropractic Neurology Center, we take a neuro-centric view of hypermobility disorders. Rather than focusing on hypermobility as a purely structural issue, we look at how the nervous system is compensating—or struggling—in response.

1. Neurological Mapping and Functional Assessment

We assess eye movements, balance systems, and frontal lobe activation to understand how the brain is processing signals from unstable joints. Patients with HSD and hEDS often show signs of poor proprioceptive integration and over-reliance on visual cues to maintain posture and movement.

2. Proprioceptive and Vestibular Retraining

Hypermobility impairs joint feedback. Through targeted brain-based therapies, we help improve proprioceptive signaling, vestibular input, and reduce reliance on overstimulated pathways that lead to fatigue or sensory overwhelm.

3. Gait and Motor Pattern Rehabilitation

Bendy joints often lead to compensatory movement patterns. By retraining motor maps through cerebellar and frontal lobe stimulation techniques, we restore more efficient, less fatiguing patterns of movement.

4. Autonomic Nervous System Support

Many hypermobility patients struggle with dysautonomia—particularly orthostatic intolerance. We use neurocognitive therapies to stabilize blood pressure regulation, improve vagal tone, and reduce sympathetic dominance.

5. Nutrition and Tissue Support

We offer nutritional guidance for supporting connective tissue health (e.g., vitamin C, copper, magnesium), reducing inflammation, and supporting mitochondrial function—essential for fatigue-prone bodies.

What Success Looks Like

While there’s no “cure” for connective tissue disorders, proper management can transform lives. When the nervous system is stabilized and movement becomes more efficient, patients feel:

- Less pain and fatigue

- More coordinated and confident

- Fewer dizzy spells or flare-ups

- Better mood, attention, and sensory regulation

Most importantly, they begin to trust their bodies again.

You Do Not Have to Figure This Out Alone

If you have been told your pain is “just from being flexible,” or you have received a diagnosis but no support, we are here to help you navigate this journey with science, clarity, and compassion.

Call today for a complimentary consultation with one of our chiropractic neurologists. Together, we will build a care plan tailored to your body and brain.

If you or someone you love is suffering from hypermobility and you would like to learn how chiropractic neurology can help, contact the team at Georgia Chiropractic Neurology Center today. We look forward to hearing from you.

Written by Sophie Hose, DC, MS, DACNB, CCSP

Peer-Reviewed References

- Castori, M., Tinkle, B., Levy, H., Grahame, R., Malfait, F., & Hakim, A. (2017). A framework for the classification of joint hypermobility and related conditions. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 175(1), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31539

- Malfait, F., Francomano, C., Byers, P., et al. (2017). The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 175(1), 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31552

- Celletti, C., & Galli, M. (2020). Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome and Joint Hypermobility Syndrome: A Single Center Experience. Autonomic Neuroscience, 225, 102662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2020.102662

- Eccles, J. A., Owens, A. P., Mathias, C. J., & Benarroch, E. E. (2020). Dysautonomia in the joint hypermobility spectrum disorders and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: An under-recognized association. Autonomic Neuroscience, 224, 102637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2020.102637